Mini-grids remain one of the most powerful tools for bringing electricity to unserved and underserved communities across Africa and they can operate through very different organizational and ownership structures. As a developer, the model you choose can determine whether your project succeeds or fails.

The difference between a sustainable mini-grid and one that collapses after a few years is sometimes not the technology, it is the operator model.

In simple terms, mini-grid operator models differ based on:

- Who owns the generation and distribution assets

- Who operates and maintains the system

- How tariffs are set and collected

- And how the relationship with customers is managed

It is useful to note that there is no “best” model because what works in one country or community may fail completely in another.

The right model depends on the local socio-economic context, the policy and regulatory environment, investor appetite, and community structure.

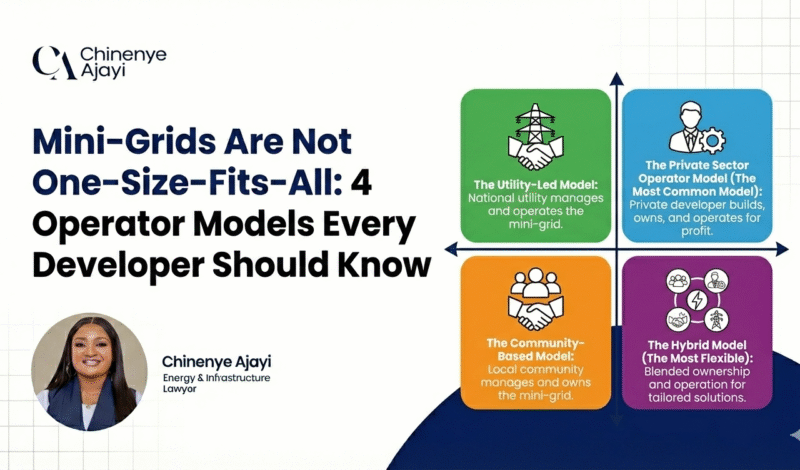

In practice, four main models are commonly used.

1. The Utility-Led Model

In this model, the national or regional utility is responsible for developing, owning, and operating the mini grid. Funding is usually provided or supported by government, and the mini-grid is often integrated into the utility’s distribution network. E.g. Kenya

Power generated from the mini grid is fed into the utility’s system and supplied to customers, usually at the same tariff as grid customers. This allows the utility to cross-subsidise tariffs between grid and off-grid customers.

For this model to work well, there must be a strong legal and regulatory framework that mandates or encourages utilities to operate mini-grids, because most utilities do not naturally see mini-grids as profitable.

Advantages:

This model provides stability, regulatory clarity, and affordability for customers. Tariffs are usually lower and predictable, and communities benefit from the backing of a large, established institution.

Disadvantages:

Utilities are often slow, bureaucratic, and financially constrained. Mini-grids may not receive priority, innovation may be limited, and expansion can be very slow.

This model works best in countries with strong utilities and supportive regulation.

2. The Private Sector Operator Model (The Most Common Model)

This is the most widely used model today. Here, a private developer plans, finances, builds, owns, and operates the mini-grid. Funding typically comes from a mix of equity, loans, grants, and government subsidies.

The private operator also sets tariffs usually within a regulatory framework. In Nigeria, for example, there is a mini-grid tariff methodology that protects consumers while still allowing investors to recover their costs.

This model can take many forms. Sometimes a mini-grid serves several neighbouring communities. Other times, it is built around an anchor customer such as a factory, telecom tower, or agro-processing plant, with excess power supplied to nearby households.

Advantages:

This model is flexible, innovative, and fast. Private developers are more efficient, more customer-focused, and better able to attract capital and scale projects.

Disadvantages:

Tariffs are often higher than utility tariffs, which can create affordability challenges. Returns can be uncertain, and projects may struggle if demand is lower than expected or if regulation changes.

This model works best where there is clear regulation, investor protection, and predictable demand.

3. The Community-Based Model

In this model, the local community owns and manages the mini-grid for its own benefit.

In reality, communities rarely develop these projects alone. Government agencies, NGOs, or development partners usually provide funding and technical support, while the community contributes labour, small payments, and local governance. The payment by the community is critical for the maintenance for the minigrid, replacement of parts and general day to day operations.

Management is often done through cooperative societies or community energy committees or through a third party organization to collect tariffs and handle basic operations and maintenance.

Advantages:

This model creates strong local ownership, high community acceptance, and long-term social sustainability. Customers are more willing to pay when they feel the system belongs to them.

Disadvantages:

Communities often lack technical, financial, and managerial capacity. Without strong support and governance, systems may deteriorate, revenues may be poorly managed, and reinvestment may not happen.

This model works best for small systems, donor-funded projects, and tightly-knit communities with strong leadership structures.

4. The Hybrid Model (The Most Flexible)

The hybrid model is simply a combination of any of the three models above. This is where creativity becomes very important.

Examples include:

- A utility owning the assets while a private company operates and maintains them

- A community partnering with a private developer

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) where government and private investors share ownership and risk

- Renewable Energy Service Company (RESCO) models where government buys the asset and contracts a private operator to run it. Under this model, ownership, operations, and revenue sharing can be structured in many ways depending on the project’s needs.

Advantages:

Very flexible. Risks and responsibilities can be shared. Public funding can attract private capital, and private expertise can improve performance.

Disadvantages:

More complex to design and negotiate. Governance can be unclear if roles are not well defined. Poor contract design can create disputes and project failure.

This model works best when there is strong institutional capacity and well-designed contracts.

Closing

One of the biggest mistakes in mini-grid development is assuming that one model fits all situations. The right operator model to adopt must fit:

- The country’s regulatory framework

- The community’s socio-economic structure

- Investor expectations

- Demand profile and affordability

- Long-term sustainability

For anyone looking to enter the mini-grid space (developers, investors, policymakers, or community leaders) understanding these models is not optional.

It is foundational.

Reference:

Minigrid Policy Toolkit (Policy and Business Frameworks for Successful Minigrid Roll Outs)